Reviews

Brent Marchant

November 19, 20246.0

From 1948 to 1957, author James Baldwin relocated from New York to Paris in hopes of finding a more fulfilling life, both personally and creatively. But what was that experience actually like for a young African-American man who had grown wary of the relentless discrimination he had faced in his homeland, both on the basis of his race and sexual orientation? That’s what this documentary-style release attempts to envision, following a young Baldwin (Benny O. Arthur) in his explorations of the City of Lights, told from an impressionist standpoint primarily in cinema verité format made to look like vintage archive footage. The result is an experimental, decidedly ambitious undertaking from writer-director Yashaddai Owens that works beautifully on some levels but misses the mark on others. “Jimmy” effectively captures the curiosity and wonder of a wide-eyed adventurer exploring a new world, one in which he’s able to enjoy freedoms that weren’t accessible to him in America. It’s a place where he could now feel a sense of liberation unlike anything he had experienced before. However, in depicting these revelations, the filmmaker puzzlingly seems to run out of material unexpectedly quickly, a rather perplexing outcome for a picture with scant 1:07:00 runtime that features an innately flamboyant, charismatic protagonist in a rich, culturally and artistically diverse environment. Instead, the narrative falls back on a lot of footage that feels more like filler than insightful and engaging imagery. In addition, having been filmed in modern-day Paris, far too little effort has been made at trying to conceal or exclude anachronistic elements that get caught on camera, an oversight that some might call nitpicking but that occurs all too often to ignore. Some aspects of Baldwin’s character receive short shrift, too, such as precious little attention paid to the emergence of his gay lifestyle, an element that almost feels intentionally underplayed. The same can be said about his observations of life and the world, material that adds much when incorporated into the film but that is employed far too seldomly for my tastes. However, perhaps the most bewildering element here is the production’s inclusion of a somewhat lengthy home movie-style travelogue of Istanbul at the film’s outset with no images of Baldwin anywhere in sight. While it’s true that the author lived in the Turkish metropolis on and off for many years, he didn’t spend time there until after his days in Paris, so the presence of this footage is quite baffling, ill-timed and, ultimately, fundamentally extraneous. To be sure, “Jimmy” is to be commended for its casting of a lead who bears an uncanny resemblance and demeanor to the picture’s protagonist and for tackling an undertaking as audacious as this, but the end result comes across as a case of the filmmaker’s reach exceeding his grasp for a project that, sadly, deserves better.

Recommendation Movies

Color Book2024

Escape to Passion1970

Kairos Dirt and the Errant Vacuum2017

Praktikum - Der Film2018

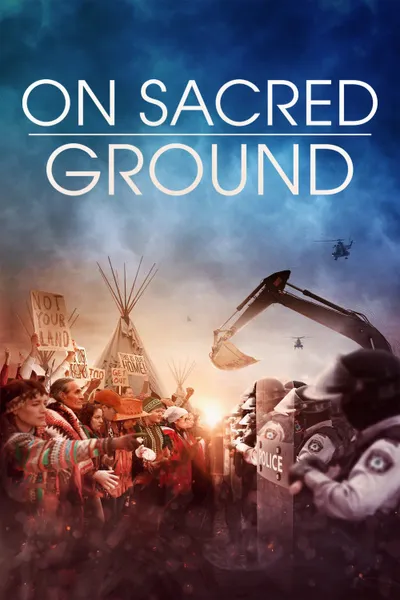

On Sacred Ground2023

Phish -1995-06-19 - Deer Creek Music Center, Noblesville, IN2021

minicômios

Story of... Cheese2016

The Man Who Killed James Bond2019

Doctor Who: The Leisure Hive1980

Caught in a Trap2008

Blood & Orchids1986

Outer Reaches2023

Saat Menghadap Tuhan2024

MABAYN ASAWAHIL2024

The 8:37 News2019

Are These Our Children?1931

Il tacchino prepotente1939

© 2025 MoovieTime. All rights reserved.Made with Nuxt