Reviews

Stephen Campbell

May 15, 20194.0

**_Just didn't work for me_**

> _I had a line that used to end the film but I ended up cutting it out. It said: "film is the art of conjuring ghosts, not getting rid of them." I used to think filming could act like a kind of catharsis and exorcism: you film to try to get something off your chest so that you can get rid of it. But I never found it to play out that way, because by making a film you're essentially creating a ghost that you're going to live and travel around the world with, and talk to people about. Essentially, you're making something that will live on - you're not getting rid_ _of anything. So, it wasn't really cathartic at all. That said, I already felt a certain peace in my relationship with my father before I started making the film. I wasn't in a turmoil trying to work it out, so to speak. But I did feel like there was some unfinished business to attend to, and I wanted to know more about him and his world, and looking back I feel as though I did build something which now has its own existence in the world, and there's something really satisfying about that. But it’s always an unfinished process. I was thinking a lot about the idea of reconciliation when I was making the film. Reconciliation between me and my father, between North and South, between his time and mine. I thought a lot about what it is like to place one image next to another. There's always something missing in between, a weirdly primal desire of wanting to make a whole out of what is not. It's almost like the idea of going back to the womb - a certain desire that can never truly be fulfilled._

- Donal Foreman; "The Personal and the Political: An Interview with Donal Foreman" (Leonardo Goi); _Mubi_ (May 14, 2018)

For me, if a documentary gets a theatrical release, there must be a tangible reason as to why. By that I mean, why was it released in the cinema, as opposed to on television, which, in terms of how audiences engage with the mediums, is a more natural home for the documentary form, where a film can find a much larger audience over a longer period of time. There needs to be something, anything, that makes the documentary inherently cinematic in some way. The majority of documentaries don't provide such a reason. For example, two films that spring to mind are Dror Moreh's _The Gatekeepers_ (2012) and Laura Poitras's _Risk_ (2016). _The Gatekeepers_ is about Shin Bet, whilst _Risk_ tells the story of Julian Assange's self-imposed exile in the Ecuadorian Embassy in London. The first, which I actually quite enjoyed as a documentary, is a series of visually drab talking-head interviews with the six still-living former-heads of Shin Bet, and the second is a poorly edited and narratively confused valorisation of its subject. Neither feature anything to justify their theatrical release. Compare this to documentaries as varied as, say, Kevin Macdonald's _One Day in September_ (1999) or José Padilha's _Ônibus 174_ (2002), with their thriller-esque narratives, plot-twists, heroes, villains, and governmental corruption and conspiracy; David Sington's _The Fear of 13_ (2015), which, despite consisting entirely of an interview with one person, is visually and aurally fascinating; Werner Herzog's _Cave of Forgotten Dreams_ (2010), as aesthetically perfect a documentary as you're ever likely to see, especially if seen in the intended 3D format; or Emer Reynolds's _The Farthest_ (2017), with its awe-inspiring and deeply emotional story of the 1977 Voyager space probes.

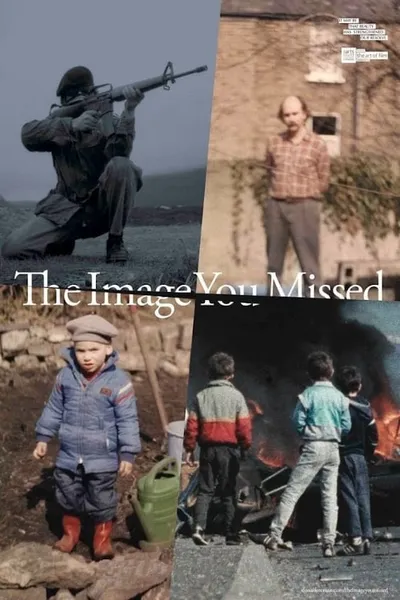

I've spent this first paragraph giving a rather wordy introduction as I want to be clear about where I'm coming from regarding my problems with _The Image You Missed_ – sadly, it is never able to justify its theatrical release; the whole time I was watching it, I was thinking to myself "why is this being shown in the cinema?" I say "sadly" because I really wanted to like it; it's a low budget documentary that takes a deeply personal approach to an inherently Irish political situation of which any Irish person over the age of thirty will have memories, and, depending on your political leanings, is either a source of great pride or deeply held shame. In short, there's a lot to root for here. Essentially, the film is a "dialogue" between director Donal Foreman and his dead father, Arthur MacCaig. An Irish-American born in New Jersey in 1948, MacCaig came to Belfast as a tourist in the early years of the Troubles, and remained fascinated with the city and the political situation as a documentarian, living first in Paris, and eventually in Belfast itself. Interested in exploring the disparity between the tribal, religious-based conflict depicted in British and American media, with what he saw as a more non-sectarian struggle between "coloniser" and "colonised", MacCaig's unapologetically Republican stance soon earned him extraordinary access to the IRA (indeed, when he died, he had a pseudo-Republican funeral – Danny Morrison and Sinn Féin PRO Joe Austin spoke, whilst Gerry Adams attended).

MacCaig's best-known film is _The Patriot Game_, a feature-length 1979 documentary made for French television, which uses street-interviews and IRA-insider material to chart the history of conflict in the province of Ulster from the formation of the Northern Irish state in 1922. Critically, the film was a modest international success, with _The Chicago Reader_'s B. Ruby Rich calling it "_the best overview of the Northern Irish conflict that we've seen_," and _The Village Voice_'s J. Hoberman citing it as "_vivid, informative, and partisan_." Closer to home, _The Guardian_'s Kevin J. Kelley praised it for "_debunking the twin myths that the IRA is a 'terrorist organisation' fighting 'a religious war'._" As is mentioned in _The Image You Missed_, when the British Foreign Office warned its embassies that _The Patriot Game_ was "_damaging and highly critical of Her Majesty's Government_," MacCaig welcomed it as "_the best review I ever had_."

MacCaig died in Belfast in 2008, when Foreman was 22. Raised in the North Strand area of Dublin by his mother, Foreman only met MacCaig a handful of times. Nevertheless, they had reconciled a few months before MacCaig died, and after the funeral, Foreman travelled to an apartment MacCaig owned in Paris to go through his belongings. Much to his surprise, he unearthed over one-hundred hours of never-before-seen documentary footage, and the idea for _The Image You Missed_ was born, as Foreman essentially tries to engage in a conversation with MacCaig by way of cutting between MacCaig's footage and his own, directly addressing his dead father, and reading in voiceover letters written by MacCaig (indeed, the whole enterprise could be labelled epistolary in design).

In this sense, both the poster and the opening credit read "_A Film Between Donal Foreman | Arthur MacCaig_". Not "a film by", or "a film about", but "a film between". The official website describes the film as a "_documentary essay_", and this cannot be overemphasised. This is, at the most basic level, a film in which someone still living attempts to 'communicate' with someone already dead (although not, obviously, in a séance kind of way). With that in mind, the film has no discernible narrative as such, using editing to juxtapose, contrast, comment upon, and suggest thematic links between the footage shot by the father and that shot by the son. The narrative jumps back and forth fairly randomly amongst MacCaig's footage, employing what could be termed "thematic editing". There's also no real central character; the documentary is not 'about' either man in the classic sense of the term; it's about the space between them.

Unfortunately, for me, it just didn't work. Apart from the already alluded to lack of theatrical justification, which really can't be overstated, one of the biggest problems was the failure to contextualise anything on screen; the tendency to jump in and out of scenes without even remotely attempting to suture the viewer into the _milieu_. Granted, it makes no claims to be an informative historical overview, but the viewer still needs to be situated in some way, shape, or form in relation to what they're watching. Foreman doesn't use the backdrop of the Troubles to inform the dialogue between himself and MacCaig, but neither does he use that dialogue to inform the presentation of the Troubles, so the fact that the film is set in Belfast is, bizarrely, and quite paradoxically, kind of irrelevant. Foreman, however, has argued that the interaction between the personal and the political is a central connective tissue in the film; speaking to _The Irish Times_, he states,

> _if it had been just about my father and my relationship with my father, without those added layers about politics and history and cinema to engage with, I don't think I would have made the film. I saw his archive as a pretext to grapple with a lot of interesting questions and challenge myself as a film-maker to deal with political questions that I hadn't found a way to do in my films before._

Unfortunately, there's little evidence of this in the film, with the Troubles never being examined beyond that of an intermittent surface-level presentation.

Tied to this is the single biggest issue I had with the film, a question I found myself asking after about twenty minutes – why should I, or anyone else, care that Foreman had a tough relationship with his father? Who doesn't? I wouldn't expect anyone to sit through a documentary in which I work out my daddy issues, not unless those issues speak to a more all-encompassing truth, and I'm really not sure why Foreman should be any different, as he certainly provides no such reason in the film. And precisely because he _doesn't_ allow the personal and the political to inform one another, the film just comes across as a guy with a camera watching old footage shot by his dad.

Maybe I didn't respond correctly to the form, maybe I wasn't the target demographic (at the screening I attended, I was the youngest person in the cinema by a good ten or fifteen years at least, and I'm 40), I'm not sure, but whatever the case, I was just left wondering as to what the purpose of any of it was.

Recommendation Movies

Under the Tree2017

Green Book2018

Lady Bird2017

Me Before You2016

Parasite2019

A Star Is Born2018

Joker2019

A Quiet Place2018

Captain Marvel2019

Avatar2009

Arrival2016

Marriage Story2019

Little Women2019

Spider-Man: Far From Home2019

It2017

They Live1988

Steve Jobs2015

Whiplash2014

One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest1975

Ocean's Eight2018

© 2024 MoovieTime. All rights reserved.Made with Nuxt