Reviews

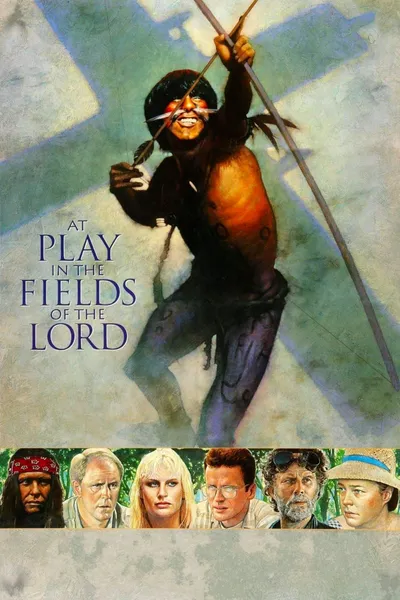

tmdb28039023

August 30, 20227.0

At Play in the Fields of the Lord is shot through with rich, complex irony (two characters, for instance, discuss having Indian blood, but while one is talking about having it in one’s veins, the other is talking about having it on one’s hands).

Its main characters, except one whose hypocrisy borders on cognitive dissonance, are torn between perception and reality – struggling in vain to have their thoughts and deeds, their words and actions, meet halfway.

Four of them form two couples that are in and of themselves counterintuitive; after all, Aidan Quinn and Daryl Hannah would make more sense than John Lithgow and Hannah, or Quinn and Kathy Bates. The only pairing that seems to belong together is that of Tom Berenger and Tom Waits.

Perhaps the most conflicted of them all is Berenger’s Lewis Moon – a “half-breed Cheyenne” mercenary hired to drop bombs on a native tribe’s village deep in the Brazilian Amazon River basin; he thinks better of it, though, after evangelical missionary Martin Quarrier (Quinn) calls his attention to the similarities between the Plains Indians and the Niarunas (“the Sioux word for ‘Great Spirit’ is ‘Wakantanka,’” and the Niaruna word is ‘Wakankon’ – now, the Niarunas are fictional, but I think the point is valid nonetheless. Having said this, Quinn’s idealistic preacher will later be sorely disappointed when he finds out about the similitude between his own Jesus and the Niarunas’ ‘Kisu’).

Moon then goes to live with the Niarunas, but whereas he may have dispensed with the white man, the white woman, specifically Hannah, retains her allure, and a brief exchange of fluids later, Moon introduces the flu into the village; thus, in a perverse twist, he manages to unwittingly find a more subtle and effective means of destroying the Niarunas.

The film, co-written and directed by Héctor Babenco, is filled with this sort of poetic paradoxes through which the characters learn the hard way that the road to hell is indeed paved with good intentions.

PS. Lithgow is excellent as a holier-than-thou prick who views his ministry as a competition with the local catholic priest, and Bates is perfect as a prude who despises the natives almost as much as she loathes herself (few can descend into madness as well as she does), but Quinn (also pretty good elsewhere) is the star of my new all-time favorite movie moment (at least until further notice).

It’s a scene with Martin and his child Billy (Niilo Kivirinta, nine years old at the time, in his only credit). Billy’s line is “Why were they doing that?”.

I only picked this up the second time I watched the movie, but you can actually hear Quinn saying “Why…”, after which the kid immediately catches on and follows through.

Now, not only does Quinn give Kivirinta his cue, but does it almost as if on cue himself (he doesn’t look at the child; instead, he looks over his shoulder, as if gazing outside the shot, in the process accidentally, or as I see it, serendipitously, turning toward the camera, so that we can also see his mouth moving); there is no pause, no benefit of the doubt. Who knows how many takes they did before they finally settled on this fourth wall-breaking solution.

The result is a little meta-textual moment wherein the relationship between the characters is solidified through the actors’ interaction – it’s not just the caring father and his beloved son; it goes beyond that, revealing the adult performer looking out for the inexperienced one.

I always suspected Quinn to be a hell of a nice guy in real life, and this incident confirms my suspicions; he and Babenco – who already had Pixote and Kiss of the Spider Woman under his belt – risked looking sloppy in order to get through the scene, which they deemed important enough to warrant this slip, and strong enough to survive it.

Recommendation Movies

The Wind That Shakes the Barley2006

Queenpins2021

Sniper1993

The Quest Fulfilled: A Director's Vision2003

Captain Marvel2019

Joker2019

Inception2010

Call Me by Your Name2017

Avatar: The Way of Water2022

The Avengers2012

Barbie2023

Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 32023

Suicide Squad2016

Oppenheimer2023

Iron Man2008

Fight Club1999

Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga2024

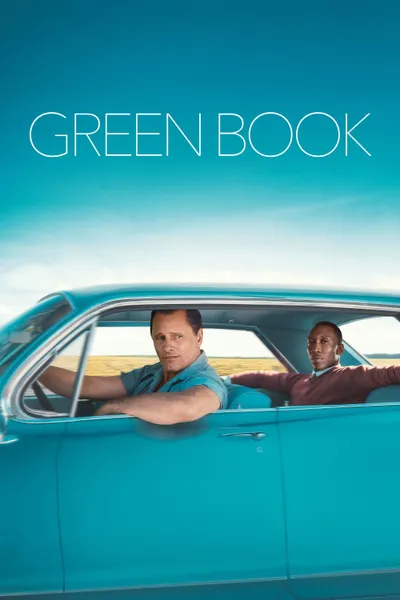

Green Book2018

Ghostbusters1984

Thor: Love and Thunder2022

© 2024 MoovieTime. All rights reserved.Made with Nuxt